In the spring of 1960, I went to England, as an “au pair”. It was not a real choice. I had chosen the wrong career orientation, and I had realised that the job of primary school teacher that I was training for did not suit me in any way. While waiting to begin my study of literature at university, I would spend 6 months perfecting my English, which I had never really had the opportunity to speak.

It was a big leap into the unknown. At the age of nineteen, I had never left France. Only once, when I was twelve, had I crossed the boundaries of my home province, Normandy, for a trip to Lourdes. I had never been to Paris. Everything was a worry for me, reinforced by the conviction that I wouldn’t understand a single word when I arrived on English soil. I was to stay in a family of two children, 8 and 12 years old, both boys, in London, that’s all I knew.

On the platform of Victoria Station, a tall gentleman, with brown hair, big glasses, in a raincoat, looked at me questioningly, he approached and uttered my name, with a few words of French. He was Mr Portner. I remember the ride in the car, big and very comfortable, wondering where and when we were going to arrive, less and less reassured by the large avenues without dwellings where it seemed to me that we had been driving for an interminable time. The car entered a street of neat houses and stopped in front of one of them. There was a small front garden with a border of daffodils in bloom. 21 Kenver Avenue. From a distance of decades, I can hear the crystalline note of the front doorbell, probably because it contrasted with the roughness of the bell at my parents’ grocery shop and will always symbolize the delicate comfort and hushed interior of this house, as it appeared to my 19-year-old eyes: a luxurious bijou residence, with red carpet everywhere, sofas and small lacquered furniture. I didn’t understand much, but the warm welcome offered by Mrs Portner and the children, Brian the “big one”, Jonathan “the little one”, relieved the anxiety and sadness I had felt since leaving France. No trace of the stiffness or even the reserve that I had feared so much. It was time for tea, which we took in the “morning room”, an instant immersion in the English world.

I have in my possession all the letters I sent to my friend Marie-Claude during my stay with the Portner family. The first one was three days after I arrived. I write that “Mr et Mrs Portner sont very very sympathiques,” that “Jonathan and Brian have a ukulele” and that Brian “on the very first day showed me the reaction of sunflowers to HCL”.[1] The following ones enthusiastically describe the Portners’ way of life, as I discover it, as if it were the ideal of a typical English family. But also – and I know how important this has been to me – of a Jewish family. From them, I will learn history, embodied for me, for the first time, in those who are close to me. A general feeling of an expanding world and human enrichment through shared daily life emerges from this correspondence.

It was obviously Mrs Portner that I had the most contact with, my job consisting of keeping the house, which the children and their father left after breakfast, not returning until late in the afternoon. One day, talking to my friend R. – also an au pair in another family – about the women we referred to between us, with no disrespect intended, as our “our old ladies” – they called us their “girls” – I admitted that I really liked “mine”, Mrs Portner. Blonde, a very delicate face despite being overweight, a beautiful smile, she dressed to go out with a great deal of elegance. I quickly learned that she and her husband had moved up socially without having degrees. With hindsight, it seems to me, that even though she was only 36 years old, I found she had quite a bit in common with my mother, a direct way of saying things, working-class modes of being, such as talking to a neighbour in the street, and a form of generosity, an ability to seek and say what is “fair”[2] (a word she often used). But on the other hand, I severely judged her status as a woman without a profession, devoted solely to the happiness of her husband and children, an absolute counterpoint to the destiny I wanted.

It’s an amazing, special situation to live for months in the private space of a previously unknown family, in a house whose details I knew well, being responsible for all the cleaning, with the exception of the parents’ room. I had my personal life – reading many French books borrowed from the Finchley library, going out around London with R. – and at the same time I silently immersed myself in the life of the Portners, which was lived out day by day before me and in which I would never need to intervene in any way. Too conscious of being an outside gaze introduced into a family, I wanted to be as discreet as possible, breakfasting before everyone else, reading in my room, walking a lot, all the way to Highgate or Barnet, alone or in the company of R.

After I left in October 1960, I wrote to the Portners once or twice during the academic year. In July 1961, with R. and G., another girl I met at university, I went on holiday to London. We were staying in Nether Street, not far from Kenver Avenue, where I returned. I saw Mrs Portner again, and we spent a few hours together in the garden. It seems to me that we didn’t have any further contact in the following years.

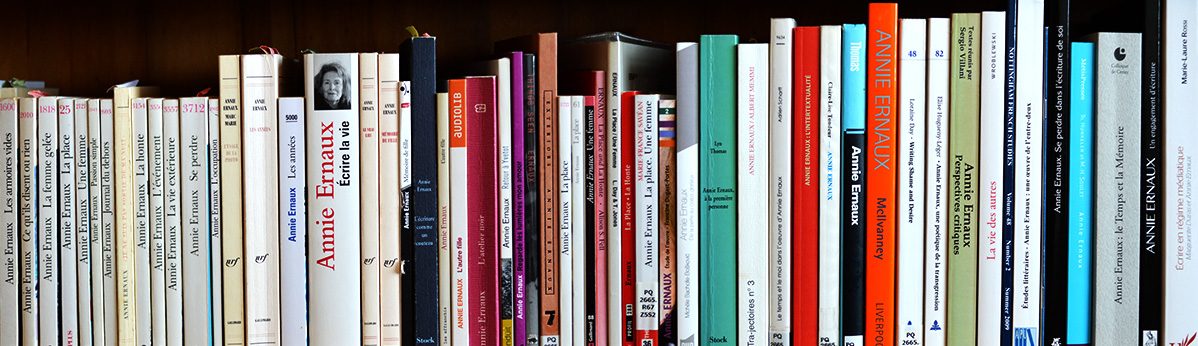

In 2014, while writing Mémoire de fille (A Girl’s Story [3]), I came to the months spent in England, which were absolutely part of this “chasm” in my life that needed to be explored. I don’t think I hesitated for long when I was choosing whether or not to write the address and name of the family where I had been an au pair 54 years earlier. Perhaps I thought that, unlike H., R. and all those whose identity I do not reveal in the book, there was no chance that it would reach Jonathan and Brian in England. A curious obfuscation of the fact that Mémoire de fille could be translated into English, which, in fact, it will be soon. Therefore, I wonder if, at some deep, hidden level, I wanted to throw a bottle into the sea, in this case to the other side of the Channel, towards those still living witnesses of a common past…

As incredible as it sounds, the bottle arrived. When I examine its route, I see a miraculous convergence of coincidences. First there is a writer and translator, Anthony Rudolf, who reads Mémoire de fille the year after its publication. He is struck by the mention of the Portners, in Finchley, as among his acquaintances there is a certain Jonathan Portner, a dentist located a few miles away. Informed by Anthony Rudolf, Jonathan Portner tells his daughter Hannah about this discovery. Now Hannah Portner is studying French with Elise Hugueny-Léger, a lecturer at the University of St. Andrews, whose thesis focuses on my work and who has participated in many conferences I have attended. Thanks to Elise Hugueny-Léger, Hannah has read and loved one of my books, Journal du dehors[4], which inspired her to create a beautiful text about Paris and Madrid: Journal de deux voyages. Observation et mise en mots du réel. Things could not have come full circle in a more wonderful way… From one woman’s writing – it was in the summer of 1960, au pair with the Portner family, that I started a novel – to another woman’s writing…

So, of course, Jonathan and I wrote to each other, with Hannah as translator, still more as a mediator between the past and the present. We made plans to see each other in Paris.

Here we are, 58 years later, on August 17, 2018, Jonathan, Hannah and I, in a café in the Odeon area of Paris, Les Editeurs. I’m sitting opposite Jonathan and Hannah, at a table close to the book shelves that justify the name of the establishment.

Jonathan is a grey-haired gentleman, in whose face and especially in whose very gentle smile – which is his mother’s – I can see the reflection of the child I knew. His voice was that of a little boy, I’m unfamiliar with his current voice. From the nineteen-year-old au pair at his parents’ house, I don’t know what he finds in the woman he has before him, except being blonde, as artificial today as yesterday. I used to bleach my brown hair, and I dye my current white hair blond as well. Face to face by chance in the underground we would not have recognized each other, strangers to each other. But we start to speak – I try, in English, with Hannah’s occasional help – and instantly something wonderful, moving happens: the past begins to live again in its most ordinary details, its anecdotes. I mention Perry, the poodle who devoured one of my shoes, Jonathan remembers me burning his mother’s nightgown when I ironed it. We evoke the layout of the house, the place of objects, the vacuum cleaner in the cupboard under the stairs, the sink in the children’s room. Above all, we talk about Jonathan’s parents who have both died, his mother, too young, from breast cancer, in her fifties.

I listen to Jonathan tell me the story of his parents, their origin, his father’s participation in the war in aviation, their rise from “having nothing” and their setbacks at the hands of an unscrupulous business associate. What I had gleaned about them – in fragments or intuitions – acquires a continuity and depth that my memories alone could not confer on them. Jonathan resurrects them with a different, more complex dimension.

For Hannah, who never knew her grandparents, or her father’s childhood home, it is the the upsurge of a time before her own, a time when she did not yet exist. Several times, I wonder how she feels as she listens to us. Because, in a way, her father and I are somewhere else, in the fever of “time regained” pronounced in two voices, where each is immersed in who he or she was 58 years ago.

Jonathan had brought pictures of him and Brian, as children, and of his parents. I hadn’t forgotten anything about their faces. His mother’s smile, his father’s presence. Then I thought that there must have been a pleasure of unutterable sweetness to be able to talk about his late parents to someone who had known them in the prime of their lives, a possibility that recedes as one progresses in life.

Before we leave, we take selfies. That’s when we notice the clock we were sitting beneath.

We head towards the boulevard Saint-Germain together. I think of London, where I walked at 19 as I walk today in Paris – which, at that time I had never seen.

Very emotional, we go our separate ways at the carrefour de l’Odéon, at the taxi rank. Saying see you again, next time, in London.

[1] Translator’s note: the first statement appears as is in French and English; the second two are in French only.

[2] Translator’s note: in English in the text.

[3] Editor’s note: Mémoire de fille has been translated by Alison Strayer under the title A Girl’s Story. It will be published in April 2020 by Fitzcarraldo Editions in Britain, and Seven Stories Press in the US.

[4] Translator’s note: while published in Tanya Leslie’s translation as Exteriors, it is important to note the echo between Ernaux’s title and the title of Hannah Portner’s text.

Previously unpublished text by Annie Ernaux, translated by Dawn Cornelio. Translation first published here on 11 April 2019.