That’s how it began with Jean-Marc Roberts, with a book he sent me in 1992 – Monsieur Pinocchio, his latest novel – which had come out the previous autumn. Inside he had written a long dedication, in that tiny writing that I would subsequently learn to recognise without fail: ‘For Annie Ernaux, having spent a good part of the night reading and re-reading her Simple Passion.’[1] And later he concluded: ‘So I salute you and your book which will never leave me.’ At that point in time, I don’t think I’d read any of his work. For me he had the face of an angel with curly hair, a highly gifted writer who, at the age of 17, had published his first novel, whereas, even at the age of 33, I doubted whether I could do the same. I had seen him on Bernard Pivot’s television programme “Apostrophes”, remaining enigmatically impassive in the face of a raging fool spouting a load of garbage about anything and everything (Marc-Edouard Nabe). When I read Monsieur Pinocchio, I discovered a tender novel flirting with indiscretion, on the verge of vulgarity without ever falling into it, as if this fluid writing marked everything it touched and described with innocence.

It was to be two years before we met again – in May 1994, in a restaurant near the publishers Mercure de France where he was an editor. This never ceased to amaze me. I had not envisaged ‘Monsieur Pinocchio’ – as he will always unconsciously remain for me – in this line of work.

In the intervening time I had read several of his books but we didn’t talk about literature. And he didn’t ask me to ‘give’ him a text, he was too discerning to do that. Instead we spoke about Italy, about Venice – I had just come back from there – and about Sicily, where he had been. He highly recommended going there which I did the following year. Above all – and this would always be a topic for us – we talked about songs, the music of French variety shows, which he had got into as a little boy, thanks to his mother, a performer. I remember that we made a bet. It was about the date on which Le Salon du Wurtemberg by Pascal Quignard had come out. I had proposed that, if I lost, it would be down to me to pay for our next lunch. I lost, but had to fight on numerous occasions before he agreed that I honour my bet, one lunchtime in a Japanese restaurant in the Rue Bernard-Palissy.

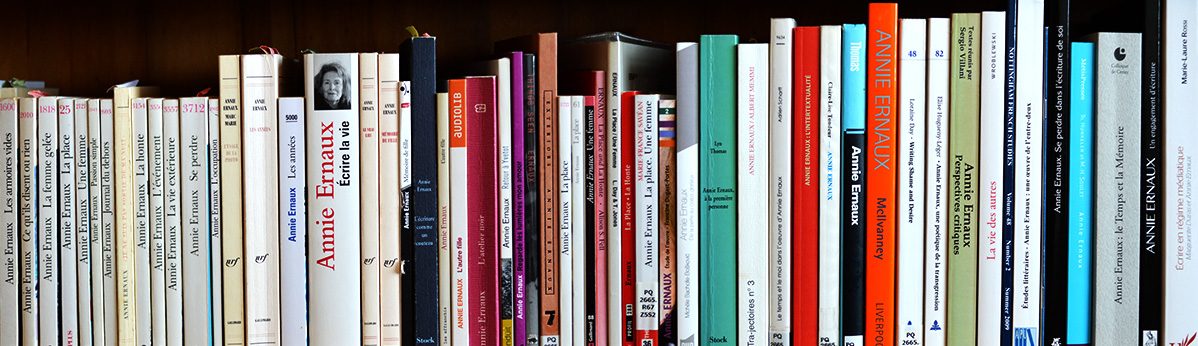

During one of these annual get-togethers, Jean-Marc told me quite straightforwardly, almost en passant, that he would be happy to publish a text of mine. And he did not go back on that. In 2000-2001, I’d had an email exchange with a young writer, Frédéric-Yves Jeannet, at that time a teacher in New Zealand. By way of his discerning questioning, he had led me to examine the whys and wherefores of my writing, in the most honest and rigorous way. I had only ever written narrative texts but this new idea pushed me to propose Writing sharp as a knife[2] to Jean-Marc, now an editor at the publishers Stock. To be honest, I was worried he would turn it down, that he would be put off by something that was neither a novel nor an autobiography. But he accepted with an enthusiasm and generosity that never waned. Two years after that book, he gladly undertook to get the work of an English academic, Lyn Thomas, translated and published. In her book on my writing she had discussed the personal readings that my texts had evoked.[3] A year and a half before he passed away, it was yet again he who decided to publish the proceedings of the conference at Cerisy which had been dedicated to me.[4] So it is strange and moving to acknowledge today that it is he, Jean-Marc Roberts, a ‘natural’ novelist, aloof from any critical theory, who brought to life texts that were not in themselves creative, but rather concerned with the interpretation of creative work: the mark of a great editor, all-inclusive, seeing beyond the short term.

He spoke about his work as a writer in a modest and light-hearted way. He expressed his wish to delve further into the truth with each book, to write closer ‘to the knife’s edge’, as he put it. These words became for us an expression of collusion, a private joke, that little by little extended beyond the field of writing to encompass the whole of life, signifying resistance to stupidity and evil – and, latterly, to illness. In a text message, he had brandished it with an exclamation mark, in defiance of the death he was facing, to which he refused to cede victory, by continuing to write and to love.

More than ten years have gone by since I saw Jean-Marc for the last time, in a restaurant in the 9th arrondissement where he was now living. He seemed to me suddenly so tall, due to the hat he was wearing to hide his head, bald from the chemotherapy, a mark of dignity, almost of classical majesty, arousing both admiration and heart-ache. He spoke about the woman who would be the last in his life, about the book he was finishing.

It is never this last image which appears spontaneously when I think of him, but another, one of pure joy. It was in Toulouse, at the ‘Marathon of Words’, in 2008, in the evening. I had abandoned the official cocktail do to join a party of authors from Stock gathered around him in a brasserie in the Place du Capitole. It was like a big family meal with eating, drinking and laughter – and even singing. Jean-Marc got to his feet and led the table in a stunning round of vaudeville songs, moving from Jean-Jacques Debout to Johnny Hallyday, whom he imitated to perfection. An astonished Pascale Roze, next to me, commented on the privilege of being there and of experiencing this moment. What struck me, what was suddenly obvious, was – as she had put it – that ‘literature is also a celebration’. At least, that was what one experienced with Jean-Marc.

In the shock and disbelief of arriving on this icy cold March morning at the Montmartre cemetery, after standing about for hours, in front of a grave so deep that the hyacinths I had brought from my garden sounded like stones falling on the coffin, it was these last words of a song which came to me, a song by Jean Ferrat from a poem by Aragon:

Like a star shining from the deep.[5]

[1] NdT/Translator’s note: Simple Passion, trans. Tanya Leslie (Seven Stories Press, 1993)/ Simple Passion, trans. Tanya Leslie (Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2021).

[2] NdT/Translator’s note: L’Écriture comme un couteau (Stock, 2003). This text has not yet been translated into English but is the translation of this title used on this website.

[3] NdT/Translator’s note: Thomas, Lyn, Annie Ernaux, à la première personne, trans. from the French Annie Ernaux : An Introduction to the Writer and her Audience by Dolly Marquet (Stock, 2005).

[4] NdT/Translator’s note: Best, Francine, Bruno Blanckeman & Francine Dugast-Portes, with Annie Ernaux’s participation, Annie Ernaux : le Temps et la Mémoire (Paris : Stock, 2014).

[5] NdT/Translator’s note: This is my translation of the last line of this poem/song which has not been translated into English. See https://lyrics.az/jean-ferrat/ferrat-chante-aragon/jentends-jentends.html and listen to at https://secondhandsongs.com/work/184079/all

This piece was originally published in French in ‘« Je vous ai lu cette nuit » : Hommage à Jean-Marc Roberts’ (Paris : Albin Michel, 2023), pp. 75-78. We translate and publish it with Annie Ernaux’s kind permission. Translated by Jo Halliday. First published here on 29 May 2024.