Among the few old family photos in my possession is one of my parents’ wedding in 1928. It shows the two lines, the two “sides”, arranged in three rows, the first sitting in chairs, the second standing, the third probably up on a bench. Men and women alternate back and forth. Two families composed of peasants (my grandparents), labourers (my parents, uncles and aunts). Everyone is dressed to the nines, women in light-coloured dresses, men in dark suits. Eyes fixed straight ahead, closed mouths, at attention in front of the lens. In the front row, their hands are clearly visible, all large and strong, resting on their knees, or placed on top of each other. Their fingers are folded inside their palms. Unoccupied hands, clenching, unaccustomed to doing nothing. Every time I looked at this photo, I had difficulty looking away from those hands, wide and powerful, both the women’s and the men’s. I come from these people and from a world in which work had only one form and only one meaning: to work with one’s hands.

Here I look at all these pictures of children at work, of women in overalls in workshops, of men bent over shovels, burdened with a yoke. Anonymous beings, living in a time when I did not yet exist, and who move me nonetheless: I recognize them. What I mean is that their bodies, their postures, their gestures are part of my legacy. The words they write on strike signs are part of my story. These photos awaken an almost physical memory, one that all the objects collected in a museum, in history books, would be incapable of reviving, the deep memory of work. Memory held within my grandparents’ and parents’ stories, told at the family table on holidays, sketching out life’s two spaces – the fields and the factory, telling about leaving school at the age of twelve, about being sent to work on farms, and then getting into the cable factory, the textile factory, the barking and bullying of the foreman, the cold of construction sites. A memory that is in the language, in the words and expressions that fly spontaneously – “we’re not on the clock!” – weaving together the ordinariness of daily life and needs, single-handedly defining an entire world and carrying a weight that can never be felt by someone who hasn’t heard them uttered repeatedly, someone that doesn’t know that having “clean work”, “inside work”, “bad weather days”[1], are privileges, doesn’t know that “débauche” means the end of the working day and that “être débauché” has nothing to do with debauchery and everything to do with being out of a job. In the general comments made to children, “work hard in school”, and in threats made to teenage girls, “I’ll send you to work in the factory, you’ll see!” A memory wavering between pride and humiliation.

Like any photo, one that represents an individual at work, more than any other, tends to enclose the person looking at it in the contingent vision of a being there, captured in the gesture as well as the décor, detached from the rest of society. It doesn’t share the noise, the smells, the pace, the factory whistle. The wages. The validation or stigmatization of the task performed. However, more than any other kind of photo, it represents society’s economic structures. Images of industrial work in the first half of the 20th century exude order and discipline, which were the foundations of Taylor’s Principals of Scientific Management whose aim was to give each individual a specific place within a division of labour. As in convents where signs of the secular world are banished, where everything must point to God, nothing within the workshop walls evokes any kind of life other than a worker’s. The décor, stripped down, austere, refers only to production. The parallelism of the bodies, the gestures and even the eyes lowered on the work correspond to the alignment of the machines. Clothing underlines the worker’s belonging to the factory, makes it uniform, like the cap which, with the overalls, the canvas bag and the lunch box, symbolizes the male working-class condition as opposed to “white collar” status. If time isn’t visible in a photo, an immobilized temporality, it can be felt in this organization of space, in this symmetry, an infinite repetition and lack of future, seeming to forever rivet each individual to their loom or his machine. Paradoxically, the closed-off nature of the place of production, the confinement of the workers is more evident, uncomfortably evident when, for the photo, the men and women interrupt their task, suspend their movements and turn towards the lens, astonished or smiling. In this fleeting and brutal emptiness, no longer acting subjects, they become objects looked at as from another world, the world outside the company.

What is most poignant for me lies in the vision of children harnessed to machines, with precociously mature and serious faces, when, at the same time, the offspring of the Parisian bourgeoisie are playing in the Luxembourg Garden, the theme of literature’s golden childhoods, from Proust to Sartre. The game ended early for those who passed from the schoolmaster’s to the factory whistle, as eight-year-olds in Taiwan do today when they make T-shirts for children in the Western world to wear. And no teenage daydreaming. Obligation to bow to the necessity whose words I can still hear: “Parents couldn’t afford to feed us for doing nothing” or “At your age, I was already working”. Undoubtedly no revolt, since the principles of order and discipline in use in the manufacturing world were already instilled in the bible of the perfect Third Republic citizen, Le Tour de la France par deux enfants. A book whose every page hammered home the value of work by carefully ignoring the word strike, made the categories rich and poor natural and absolute, assured everyone was in their place: “As you passed through the outskirts of the city, did you see the tall, poor-looking houses, where you could hear the active sounds of tradespeople? This is where the large working-class population lives. Everyone has their own small dwelling or workshop, often perched on the fifth or sixth floor, equally often sunk into the ground, and they work all day sending the shuttle between the silk threads. From these obscure dwellings come shiny fabrics, with all kinds of colours and designs that spread throughout the world.” So says Mr Gertal, the good merchant, the ideology’s own spokesman, to good little Julien, the future model worker.

The perverse effect of photography whose plates are simultaneously imprinted with our myths and reality. There’s no avoiding that a gathering of workers in the enclosed space of a factory looks like a prison or hell, just as the reaper in a field brings up biblical and poetic images, the baker’s movements seem more noble, more creative than worker’s on piece work. On the one hand meaning, on the other anomie. As much fatigue, nonetheless, and repetition. We can’t forget that at the beginning of the century, many people aspired – my people aspired – to leave the earth, to escape the sun and the rain. That working in the shelter of workshops and factories, with a fixed schedule, without isolation, subjected to a foreman’s direct domination represented progress.

We especially can’t forget that the workshop and the factory played a liberating role for girls and women forced to earn a living. This enclosed space where they are kept locked up is an “outside” in relation to the home, family, their own or that of others when they serve as “domestics”. At a time when a woman’s assigned destiny is taking care of her husband and children, when good novels never depict a young girl going out without a chaperone, a factory worker, with her hair down, can move freely, is unfamiliar with loneliness or domestic confinement. She tries out a mixed-gender space and camaraderie at work, unity in struggle. The force of the stigma of the feminine form of factory worker (“ouvrière, an ungodly word!” declared Michelet), which, unlike grisette or midinette[2], did not arouse literary idealization is proof enough that its existence and its role are transgressive. Certainly, in previous centuries, the women of the common people, the peasants, always worked, but it was in the 20th century that they began to occupy paid jobs and to work in real occupations, to participate in previously male fields. 1908’s first female poster hanger has gone down in history. Breaking the stereotypes attached to femininity, fragility and weakness, she moves forward quietly and robustly, carrying her bucket and ladder, solidly sitting on her shoulder. You can just picture her, perched on a ladder rung, carefully applying the ad for the latest show to the wall, shrugging off the taunts. Like a lamplighter, whose urban counterpart she is, the city belongs to her. It is her right to occupy it, not as a place of passage, as it is for women who buy or stroll, or who traffic their body, as prostitutes, but a space where she takes action. At the other end of the century, female bus drivers will also travel the city’s roads in the same quiet way.

These conquering images, however, cannot mask the persistence of a sexual division of labour. If, during the First World War, women replaced men in all types of work, when peace came they were invited to go back to their “natural” place, the home. In the great Parisian cafés, they returned their aprons to the men who reclaimed them along with their trays and have kept both to this day in establishments whose prestige is marked, among other things, by having exclusively male servers. And if women are seen making miner’s lights, flying planes, men are not seen ironing clothes, very few are hunched over sewing machines, even fewer, later on, over typewriters, until computers achieve some equality in the use of such a tool, though not in its tasks. Because women share men’s work, are associated with economic life, but men do not share the work traditionally attributed to women. I notice, unsurprisingly, that, in this examination of work in the 20th century, something huge is missing, the unpaid, invisible, work that melts into the background of society which it nevertheless maintains and perpetuates, the work done essentially by women, cooking, cleaning and childcare.

Everything happens as if practices used in the private sphere were transferred into the manufacturing world. Wood and metal for men, fabric for women. More often than men, women in photos appear obediently seated at tables, eyes lowered, applied to tasks that occupy their hands. Forced into a bodily immobility in contrast with their fingers’ agility. Insidiously, women are called upon to perform what is thought to be their nature as a woman, to match their activity and their image of weakness and delicateness, of devotion and self-denial even. From the 1960s onward, women’s massive participation in teaching and in the service sector meets this need to maintain femininity, to have “proper woman’s work”. But these images of supposed femininity are torn apart here by the reality of the robustness of the photographed bodies, reminding us that in the world of peasants and workers, women’s strength and resistance have long been considered values and being in “poor health” sounded like a curse. (Today, in Zaire, women known as “surrogate mothers” carry loads of fifty to eighty kilos on their backs.) The faces of women on strike, struggling with the weapons of the law instead of weapons of seduction, show the same mixture of solemnity and firmness, of pride, as those of men.

Working with one’s hands is an unsuitable expression, insufficient at the very least, it would be better to say: working with one’s body, with one’s whole body, including – inevitably – thinking (while the opposite is not true, intellectual work sections off the body). What the photos magnificently show is the body at work, the body of work. Today, when delighted – commanded-to-be-delighted – bodies; high-performing, athletic bodies; playful, self-referential bodies are the number one topic, it is salutary to show, to feel bodies at work on the world. Arms lowering a lever, hands ensuring their grip, legs spread, poised, ready to lift a bag, shoulders carrying, on a man’s back, loads that make them bend: all these postures of effort and balance, tension, used by the so-called manual worker to grapple with matter, (no rhetoric to seduce it, no metaphors to transform it) are made more than visible, noticeable. This bodily combat with the material world, captured by photography in the century’s first decades, gradually gives way to the beauty of gestures, their unusual and symbolic character, as is most magnificently exemplified in Doisneau’s The Painter. Painting with one hand, barely steadying himself with the other, like a bird between heaven and earth, he is an image simultaneously embodying Pascalian thought, boastfulness and fragility: the human condition.

This aestheticization corresponds to the decrease in the physical difficulty, in the number of “workers who use their muscles”, a category that has disappeared from language, as if the immigrant workforce that replaced the national one doing the arduous tasks didn’t deserve it. The technological boom, the scarcity of work and its transfer at a lower cost to the Third World have all contributed to concealing what is at stake in human activity, its meaning, as well as to its erasure from art and literature. The economy, the market are the dominant values, freed from their relationship to work. And there are no more workers, but rather cleaning agents, security agents or customer service agents. It is the era of isolation and anxiety coupled with enchanted denial.

Tonight, the supermarket checkouts were crowded. Repeatedly, the cashier would say a smiling hello, with her right hand push back the bar separating each customer’s items, advance the belt with her foot, grab a package, wave it in front of the scanner and then, nimbly transferring it from her right hand to her left, stuff it into a plastic bag, which she had detached from the pile of other bags and opened with an abrupt shake. When the bag was full, she would pick it up from the holder and push it towards the customer to open another one. If the product did not trigger a beep from the scanner, she would wave it several times, with both hands, slower. In the event of repeated failure, she had to type in all the numbers in the barcode. Finally, she would press a button on the cash register, then a second button depending on the type of payment. Cheques required the most handling, insertion into a slot on the cash register, showing it to the customer, writing the customer’s ID number on the back, storing it in a drawer under the scanner. She would say goodbye and then hello again, pushing the separating bar.

In my mind, I could see my ancestors’ hands in my parents’ wedding photo. It occurred to me that the common thread between generations, between the most distant past and our world today, was work. In all its forms. That it should regain its value as a link between men.

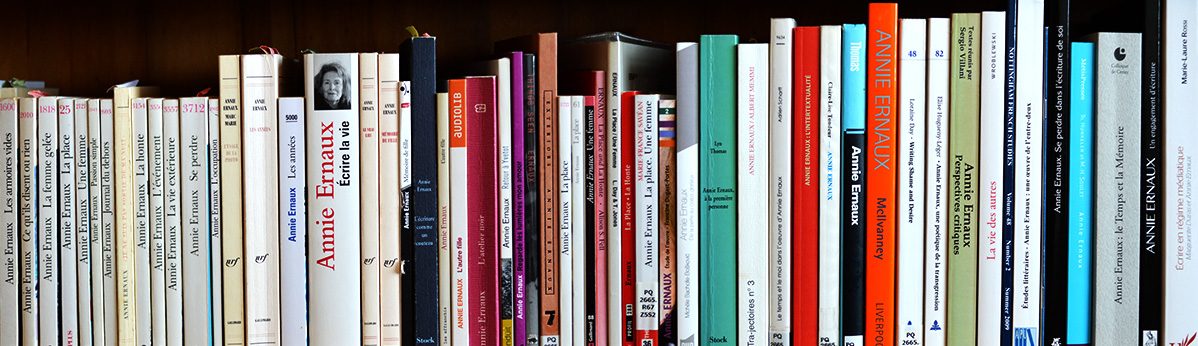

First published in Acteurs du siècle, dir. Bernard Thibault (Le Cercle d’Art, 2000), pp. 43-53, reproduced with the kind permission of Annie Ernaux. Translated by Dawn Cornelio. Translation first published here on 8 October 2018.

[1] Translator’s note: The French expression is “être aux intempéries”, to be paid for days when work is impossible because of bad weather.

[2] Translator’s note: According to the cnrtl.fr dictionary, both words refer to female factory workers; the word grisette carries the connotation of being flirty and welcoming some advances while midinette implies frivolity and naiveté.