Several years ago, a cousin I had lost touch with since I was a teenager came to visit my mother in hospital in the town where I lived, and he took the opportunity to drop by my house. At the living room entrance, he stopped dead, stunned, his eyes fixed on the bookshelves which completely covered the back wall. ‘Have you read them all?’ he asked me, incredulously, almost frightened. ‘Yes’, I said, ‘just about’. He shook his head in silence, as if this was a feat that had demanded some effort, especially when put alongside the qualifications I had obtained and the books I too had embarked on writing. As for him, he had had to leave school at fourteen, working wherever he could. His family did not have books. I only ever recalled seeing the comic book Tarzan lying around on the table.

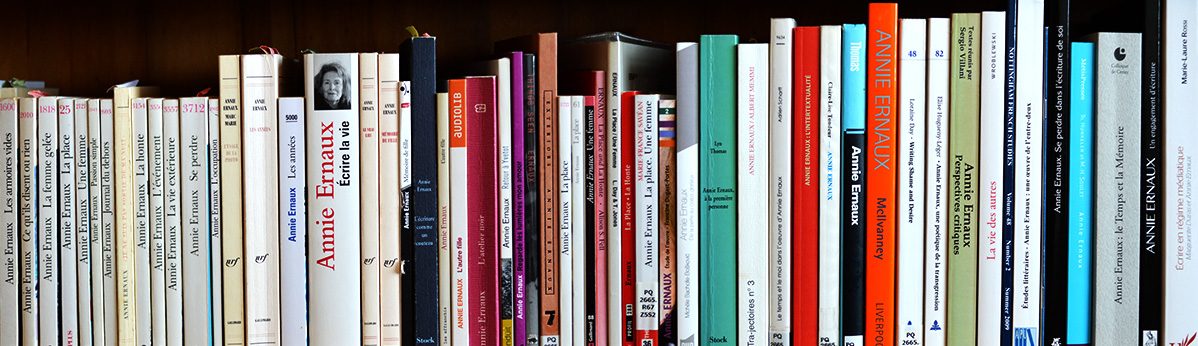

Even though yet more books have invaded the living room, no-one else among those entering since then has asked me the same question. It was not an issue for them. It went without saying, from their point of view as more or less diligent readers, that I had read most of these works, and above all that being surrounded by books was my natural element. I even wonder if some of these visitors, journalists, critics or students must have considered that, as a writer, I should have had more.

I often recall this scene with my cousin with unease. It conceals another, violent, one. I was between fifteen and eighteen years old. I must have reproached my father for ‘not being interested in anything’, for reading only Paris-Normandie, the local newspaper. Usually so calm and conciliatory regarding the insolence of his only daughter, he replied sternly: ‘Books are all well and good for you. But as for me, I don’t need them to live.’

These words stretch across time, they remain fixed inside me. Like a pain and an unbearable reality. I understood very well what my father meant. Reading Alexander Dumas, Flaubert, Camus would not have served any practical purpose in his work as a café owner and his encounters with his customers. On the other hand, in the future he envisaged and hoped for me, he vaguely knew that books held weight, that they formed part of a defining package – ‘cultural baggage’, to coin a phrase – that also included the theatre, the opera and winter sports – a superior social world. I understood all that and it was unacceptable. I refused to think that the world of books would stay forever closed to the human being who, with my mother, was dearest to me. These words signified and endorsed the separation, which I could not name, between him, farm boy at 12 years old, and me, pursuing my studies. It was as if he was turning his back on me. He was simply hurting me in the way I had hurt him. Reading, between him and me, was a reciprocal wound.

As I evoke reasons for reading, my father’s words come back to me insistently, like a personal and insurmountable contradiction. No, to read is not to live and yet I have always lived with books. I measure, with amazement, the chasm between everything that reading has meant and continues to mean for me and its insignificance, or even complete absence, in the lives of others. I cannot put myself in the place of a non-reader, even in such dark periods of my life as mourning, separation – words at these times are inadequate – or in relation to the opposite, times full of passion and happiness rendering any reading dull and inferior to the intensity of the present moment.

Ever since I learnt to read at the age of 6, I was attracted to the written word, to whatever was within my comprehension range, from the dictionary to the Bibliothèque Verte series of authors’ works adapted for young people that my mother – who herself loved reading – often used to give me. Books were expensive in those days and I never had enough. I dreamt of working in a bookshop so that I could have hundreds to hand. The pleasure to be had from reading was self-evident, alongside the joy of playing. What’s more, books played a part in my games which often consisted in me imagining being a character. In turn, I was Jane Eyre, Oliver Twist, David Copperfield, the strange ‘barefoot girl’ from a German novel (by Berthold Auerbach, according to the internet), and many more characters besides. Only a sort of unconscious censorship must be preventing me from remembering at what later age I stopped becoming, on the way to school, the heroine of the book I was reading at the time. But I definitely know the part played by the evocative power of books in my sexual awakening – and thereby hangs a tale, starting at the age of 12 with Devil in the Flesh by Radiguet,[1] which I had got hold of on the sly, attracted by the promising title. Books provided me with the situations, even the actors, to play out my adolescent eroticism, thereby justifying the claim made by the religious institution I attended that reading was the gateway to vice for young girls. (Even today, the written word still seems to me more sexually exciting than images, the text of The Story of O[2] more disturbing than the film version.)

In my teenage years, the words spoken by my father revolted and tore me apart so violently precisely because reading had become for me the quest for alternatives to received narratives, those of the convent school where I studied, as well as those of my working-class environment with its beliefs and its maxims and its respect for the established order. I search in confusion, wondering whether any one book pushed me into or provided me with new thoughts, thoughts that were all the more desirable because they were forbidden: the magic of titles such as The Immoralist (Gide)[3] or The Rebel (Camus);[4] as well as those titles that promised a search, not for lost time – at 15 there is none, Proust would come later – but an understanding of life, such as The Quest of the Absolute (Balzac),[5] The Roads to Freedom (Sartre)[6] or The Difficulty of Being (Jean Cocteau).[7] I looked for and found in contemporary novels ways of living which projected me into the future. Because reading played, at that moment of my existence, the role of an advance instalment on life (perhaps it always has, until late in life, like a struggle against death). And the desire to know what it meant to be a woman, to live a woman’s life, pushed me towards women writers such as Simone de Beauvoir and Virginia Woolf. It was the time of writing out quotations in a secret diary, like a truth about oneself and for oneself, like a handbook, and for the certainty of not being alone in experiencing the same things: the joy of there being at least two who shared a feeling and/or some consolation for the difficulty of living. With hindsight, I view the gesture of copying down sentences as if it were an affirmation of my being, steeped in reading, and with every quotation added, a protestation against the words of my father. For example, this – which would doubtless have horrified him – written in a notebook which survived all the relocations, an extract from Crime and Punishment: ‘To live in order to exist? Why, he had been ready a thousand times before to give up existence for the sake of an idea, for a hope, even for a fancy. Mere existence had always been too little for him; he had always wanted more.’[8] But how could I, at that stage of my life, have penetrated the interior world of a criminal, other than through Dostoevsky’s novel?

At that point in my life, without knowing it, I was at the very heart of the contradiction which reading represented: it separated me from my own people, from their language, and even from this me who had begun to express herself with words other than theirs. But it also connected me to other minds by means of characters with whom I identified and to other worlds outside my experience. Reading: it separates and it connects. It is first of all a concrete separation: reading supposes a break from all verbal communication, a detachment from one’s surroundings. It is also a mental separation: to read is to be transported into a new universe, whether that’s purely imaginary, such as that of Harry Potter, or the opposite, referring to sociological or historical reality, such as One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.[9] To read is to be momentarily separated from oneself and to let a fictional being – or the ‘I’ of the writer – occupy completely our interior space, taking us towards their destiny, stirring our emotions. It is to accept that a voice can break into our consciousness and take the place of our own: ‘For a long time I would go to bed early.’[10] It is also to accept being disturbed, shaken up and in the end transformed. But, in the process, reading brings us closer to others, places us in the head of the criminal Raskolnikov, of the class defector Martin Eden, inside the thoughts of Mrs Dalloway walking through London. Reading opens up a sensitivity to the way people live. And to what they have known, undergone. Since childhood, I had learnt about the existence of the Nazi concentration camps, but it is the books of Primo Levi, of Robert Antelme, and later of Imre Kertész, that sensitised me to the unthinkable and made it real. In the same way Christa Wolf’s book, A Model Childhood,[11] made me understand how Nazism had been able to establish itself and prosper in the 1930s. Reading increases the capacity to understand the world, in all its diversity and complexity. In French, lire (to read) and lier (to connect) comprise the same letters.

Reading leads back to the self. Reading in order to read oneself.

I am aware that reading no longer constitutes the fount of all knowledge as it was for me and others in the past. Like everyone else, I no longer consult dictionaries but the internet, I watch broadcasts on television about the conflicts and issues of society and watch films and documentaries at the cinema. As with a book, I get from them knowledge and escapism, pleasure and emotion. But how come the book seems to me irreplaceable? First, because of its ease of use, its plasticity. You can leaf through it, start reading at the beginning or no matter where. You can rush through the text, slow down, stop and raise your head to reflect on a sentence, abandon it for weeks and then take it up again. Reading does not fit into a circumscribed length of time. It is the freest possible cultural act. The relationship invested in a book is by its nature a very intimate one, often entered into with precision in a certain time and space, associated with moments of life and places, a town, a hotel room, a train on the way to Italy. Reading is an experience that invisibly engages the totality of one’s being: all the senses are called into play by the imagination. And what remains elusive is the voice of the book – missing in the adaptation of a novel to the screen – a voice whose tone, colour, gentleness or violence lives on in the memory.

One of the most disturbing scenes I have seen at the cinema is the final one in Fahrenheit 451, a Truffaut film. Given all books have been forbidden and burned, men and women hiding in the woods come and go, each one memorising a book by repeating it out loud.

Many years ago, in my personal diary I noted: Despair, as I have encountered it, is to believe that there is no book capable of helping me to understand what I am living through. And to think that I will not be able to write such a book.

When I was little, my father took me after Mass to the public library, situated in the Town Hall and open only on Sunday mornings. It was the first time we had gone there. Inside it was solemn, deserted, with a polished parquet floor, and a counter behind which was a man who asked us for the titles of the books we wanted. We had no idea. The man chose for me Columba by Mérimée and for my father The Rose King of Madame Husson, by Maupassant.[12] It is the only book I saw him read, at the kitchen table.

I began to write when I was about 20 years old. I sent the manuscript of a novel to an editor, who rejected it. My mother was disappointed, my father not, almost relieved. He died five years before I had my first book published. I wonder if the ultimate goal or driving force for my writing is to be read by those who normally do not read.

Translated by Jo Halliday. Annie Ernaux’s text was originally published under the title ‘Trennen, verbinden…’ in a German collection, ‘Warum lesen?’ (Why read?), which includes texts by 24 writers answering this question. We are reproducing and translating it with kind permission from Suhrkamp Verlag and Annie Ernaux. Translation in English first published here on 30 January 2021.

[1] NdT/Translator’s note: This is the title of the translation of the novel into English by Robert Baldick, Penguin Classics, London, 2019.

[2] NdT/Translator’s note: as translated by Sabine d’Estrée, Ballantine Books, Penguin Random House, New York, 2013.

[3] NdT/Translator’s note: as translated by David Watson, Penguin Modern Classics, London, 2000.

[4] NdT/Translator’s note: as translated by Anthony Bower, Penguin Modern Classics, London, 2000.

[5] NdT/Translator’s note: as translated by Ellen Marriage, Dedalus European Classics, London, 1997.

[6] NdT/Translator’s note: as translated by Eric Sutton, Penguin Modern Classics, London, 2001.

[7] NdT/Translator’s note: as translated by Elizabeth Sprigge, Melville House Publishing, London, 2013.

[8] NdT/Translator’s note: as translated by Constance Garnett, Wordsworth Editions, London, 2000. The extract is on p.456.

[9] NdT/Translator’s note: as translated by Ralph Parker, Penguin Modern Classics, London, 2000.

[10] NdT/Translator’s note: This is first line of Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, translated into English by C. K. Moncrieff and Terence Kilmartin, revised by D. J. Enright, Vintage Books, London, 2005.

[11] NdT/Translator’s note: as translated by H. Rappolt and U. Molinaro, Virago Modern Classics, London, 1983.

[12] NdT/Translator’s note: This is my translation of the title. The text has been translated into English online at http://www.online-literature.com/maupassant/242/